Why Yoga Matters – Buddhiyuktaḥ – Part One

Evenness, balance, integration: the platform for greater skilfulness. This is yoga. To cultivate it, we practise the medi-state.

Buddhiyuktaḥ -Yoga,

the medi-state and why it matters

The basic practice of yoga is meditation, the cultivation of a state of integration which is the platform for skilful, spacious, appropriate response. One useful way this state is described in the yoga tradition by Kṛṣṇa in the Bhagavad Gītā is as being buddhiyuktaḥ – at once: integrated through all the constituent powers of our awareness, and connected to ‘buddhi’, the most refined part of our awareness.

Why does yoga matter? Why is it worth making the effort to cultivate yoga, the medi-state of balance, integration and connection to the most refined part of our awareness? Life is better, richer, fuller when we can meet it buddhiyuktaḥ. We can meet it more skilfully. So what does it mean to be buddhiyuktaḥ? Why is it so helpful? Here, we will look at two complementary descriptions of this ‘joined up’, integrated state of yoga. We’ll look at the ‘map’ of the reality of our being from the Indian school of Sāṅhkya philosophy that Yoga also uses and assumes a familiarity with, and which Kṛṣṇa is referring to when he talks about being buddhiyuktaḥ. We’ll also look at the brilliant ‘hand model of the brain’ that contemporary neuroscientist Dr Dan Siegel uses to help illustrate what it means to be integrated.

Living a ‘joined up’, congruent life

Yoga is joining, or the state of being integrated and ‘joined up’.

When we are ‘joined up’ and congruent, how do we feel? Pretty good, great even. When our thought, word and deed are all aligned with our conscience, does it not feel wonderful? When we live as an expression of the true longings of our heart and soul, we feel great.

But when we are incongruent, when our thought, speech and action are not aligned, when we ignore or strategise against our conscience, we suffer.

Is this not true?

This is a foundational premise in yoga. Yoga means to connect. Life is better when we are connected to our conscience: when we are congruent, attuned, in harmony, when we are living as the true expression of our soul. When however we are disconnected, out of whack, we suffer. Disintegrated, energy and information does not circulate so freely through the circuits of our being, we become imbalanced, parts of ourselves get neglected, undernourished, confined to the shadows. We are not able to respond as skilfully to the inevitable challenges and change of life.

We humans sometimes resist change. We seem to like to cling to ‘certainties’, but most of them are false.

Some exceptions:

We are all going to die. We exist in nature: the realm of life, of birth and death, of expansion and contraction, pulsation and cycles. Between the two great changes of birth and death, what can we be certain of apart from change?

Yoga asks us to remember that as human beings with two eyes there will always be more that we cannot see than we can. Like other great systems of practical philosophy, yoga asks that we cultivate our capacity to be steady amidst uncertainty, and our capacity to admit and allow differing views.

We are much better able to do these things when we are ‘joined up’, connected, integrated, or what Kṛṣṇa, the teacher in the Bhagavad Gītā, calls buddhiyuktaḥ.

Recently, I have been encouraged to see some contemporary neuroscientists teaching some of the same yogic truths that the great research scientists of the ancient Indian tradition laid out millennia ago. Contemporary scientists like Dr Dan Siegel and Dr Bruce Lipton agree that when we are integrated, connected, joined up, we can live ‘better’: more healthily, more skilfully, more enjoyably. We can live more how we’d really like to. And further, when we are integrated, or buddhiyuktaḥ, we can deal much more skilfully with life: with the unexpected and with things that might challenge or shake us.

This is powerfully illustrated by Kṛṣṇa’s description of being buddhiyuktaḥ and by Dr Dan Siegel’s brilliant ‘hand model of the brain’. Before we consider these beautifully complementary explanations, I’d first like to set out the foundational map of awareness that the great ṛṣi-s (research scientists/seers) of the Indian tradition laid out.

The Ganglands of our Being – Tattva-s and Gaṇa-s

The Ganglands of our Being – Tattva-s and Gaṇa-s

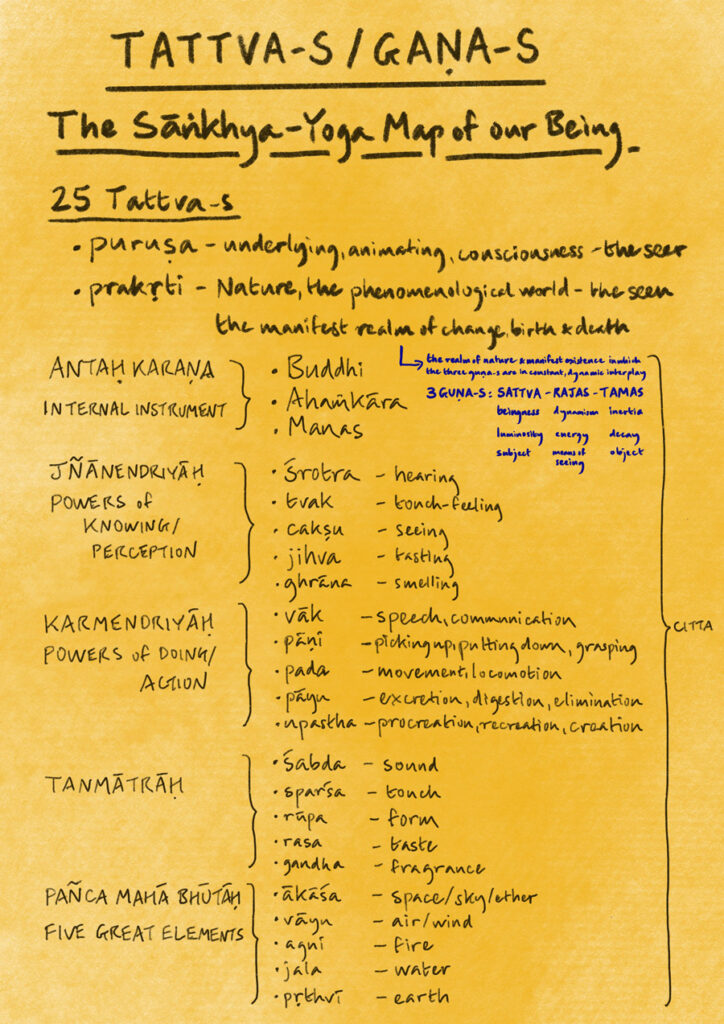

The ṛṣi-s, the great seers and research scientists of the Indian tradition, recognised that when we are conscious beings, puruṣa-s, when we come into embodied existence in prakṛti, the realm of nature, our embodied consciousness experiences through different constituent parts. The ṛṣi-s recognised that there are different members of the group of our being. These are referred to in Sanskṛt as gaṇa-s, ‘members of the gang’ that make up the collective of who we are. They are also known at tattva-s. Literally ‘thatnesses’. Tat means ‘that’ in the sense of that which is, which exists. The suffix ‘tva’ is a bit like ‘ness’ in English, ‘having the quality of’. The tattva-s/gaṇa-s all have the quality of existing in the collective of our being. Yoga is about bringing all these members of the gang of our being into dynamic equilibrium, so they can support us to meet life as skilfully as possible: enjoying, learning and growing as life unfolds.

With the model of the tattva-s, the ṛṣi-s of the Indian tradition bequeathed us a very practical ‘map’ of the ‘ganglands’ of our being. The ṛṣi-s recognised that we each contain the five elements of earth, water, fire, air and space. And so we also have and experience five associated qualities of fragrance, taste, form, tactility and sound/vibration. As sentient beings we are also endowed with amazing powers of action, which we can also describe in a group of five. One: our powers of speech, expression, communication – which for us humans includes our linguistic capacities. Two: our manual dexterity and capabilities, the ability to grasp, pick up and put down. Three, our diverse movement and locomotive capacities. Four, our powers of digestion, assimilation, excretion and elimination; and five: our creative, recreative and procreative capacities. Then we also have our five sense powers of smell, taste, vision, touch and hearing.

So far then, working from gross to subtle, we have seen twenty tattva-s, twenty gaṇa-s. Continuing in this map of our reality, we come to what is referred to in Sanskṛt as the antaḥ karaṇa – the ‘internal instrument’, which has three constituent parts. We have manas, sometimes rendered in English as ‘mind’, though this can be misleading. The manas is that part of inner or more subtle (relative to the sense and action powers) awareness that also looks out, and which links the input and experience of our sense and action powers to our inner realm. We also have ahaṁkāra. Aham means ‘I’, ‘me’. Kāra means ‘maker/doer’. Ahaṁkāra is that part of our awareness that gives us a sense of I, me, mine, of individuality. It is essential to help us safely cross the busy road, to not step into the void when walking along a cliff. Sometimes people use the word ‘ego’ to represent ahaṁkāra, but this can also be misleading. Ahaṁkāra is not an exact equivalent of the Jungian ego. There is some overlap, but it is more than that. Ahaṁkāra is also the intelligence that holds us together as an individual unit.

Here we are, as human beings, made of earth, water, fire, air and space. These elements don’t sit together so easily. If we pour water that contains earthy matter into a glass, before long they separate. If we add fire to that mixture of earth and water, likely the water may boil and evaporate, or the fire will be doused. Yet we humans cohere as this miraculous being with mutually co-existing earthy and watery and fiery parts. In our body that is predominantly water, our internal combustion engine and digestive fire generally functions very well. We are miraculous beings.

The intelligence of our ahaṁkāra is mind-blowing. It functions in ways that certainly go well beyond what we are able to compute with our minds. It also demonstrates that we have, innate within us, a great capacity for yoga, for togetherness, for reconciling that which might at first glance seem impossible to reconcile.

Buddhi – Home of discernment, key for integration

The third part of our antaḥ karaṇa – the internal instrument of our conscious awareness, is known in Sanskṛt as buddhi. This is the subtler part of our intelligence. It is this subtle power of buddhi that discerns, that makes decisions. Buddhi is the realm of discriminating, judicious awareness, the seat of our subtler capacities that help us relate to others, that enables us to hold differing points of view, to empathise, to reflect and contemplate. Buddhi is from the same Sanskṛt root ‘bodh’ that gives us the word Buddha – the awakened one. Sometimes referred to as the enlightened one.

When the light of awareness is circulating smoothly and harmoniously through the circuit of our being, through all our gaṇa-s – all the members of the gang of our whole self – we can see and experience more clearly. When the light of intelligence and awareness courses freely through the network of our tattva-s, through the whole of our neural network, we can act and respond more intelligently. When our circuit is earthed, when we are steady, easeful, spacious, balanced, integrated, we can act more skilfully, respond to unexpected and even intimidating situations with more clarity and discernment.

Yoga practice is about training this capacity to respond skilfully.

Ancient and ever fresh – perennial yogic wisdom

The other day I was talking with a friend who is a psychologist and psychotherapist about the challenges of responding skilfully in our world of uncertainty. She shared with me one of the brilliant ways contemporary neuroscientist Dr Dan Siegel describes the brain, using the forearm and hand to illustrate what he refers to as ‘the hand model of the (head) brain’. I was struck by how Dr Siegel’s perspective and work echoes the findings and teachings of the ancient research scientists of the Indian tradition. Indeed, the modern neuroscientific descriptions of the brain map well onto the model of the tattva-s, and can help us understand some of the broader meaning of ahaṁkāra and buddhi that reach beyond the English words that are sometimes used to represent them.

The hand model of the brain

(I have linked to three talks of Dr Dan Siegel explaining this at the foot of the article – below is my paraphrasing him and linking it to the yogic model of the antaḥ karaṇa)

Taking our forearm and hand, and looking at them perpendicular to the ground: from the elbow to the wrist is like our spinal column, the central information highway through which our ‘brain’ and intelligences are spread through the whole of our body, animating our sense and action capacities. The base of the palm is then like the brain stem, continuous with the spinal chord and responsible for breathing and other autonomic fuctions. This is the oldest part of our brain, (around 300million years say contemporary neuroscientists) sometimes called the reptilian brain, and it’s also the seat of the flight, fight, freeze and feint responses. If we then fold in our thumb across our palm, the area of the mid-palm enclosed by the thumb can give us a representation that also includes the next part of our brain, the limbic system, also referred to as the mammalian brain (about 200million years old). This is the seat of our basic motivational drives and the part that allows us to feel attachment to our mother and close associates.

If we then fold down our four fingers, the fingers represent the more recent part of the brain, the cortex. This part of the brain is what allows our higher linguistic capacities and our capacities, for example, to empathise and to hold, honour, acknowledge and even reconcile different perspectives and points of view.

We have these capacities, but we do not always stay attuned to them. Dr Siegel represents this by the memorable image of lifting up the previously folded down fingers. To quote him, this is like we have ‘flipped our lid’, which can happen easily when for example we become fearful, anxious, angry or dejected. The integrating, connective part of the brain in the pre-frontal cortex which when integrated connects the powers of the cortex, the limbic system, brainstem and body gets ‘disconnected’. Dr Siegel explains how we then become either ‘chaotic’, with outbursts of irrationality or reactivity for example; or ‘rigid’, shut down and withdrawn. In other words, we lose our connection to our ‘higher’/subtler capacities. We lose our connection to buddhi. In this disintegrated state, in most situations, we can no longer act optimally – running for our lives being an exception.

We flip our lid, we lose integration, we lose balance – and we disconnect from our capacity for a skilful response.

As my friend related Dr Siegel’s ‘handy’, ever-ready model of the head brain, and how the disintegration of the subtler parts of our awareness can happen so easily when we feel dominated by fear, anger or more primitive urges, I was struck by how it echoes what Kṛṣṇa, the teacher, lays out so memorably in the Bhagavad Gītā.

The story of human suffering – in 64 syllables

In 64 syllables, Kṛṣṇa distils the whole history of human suffering:

Dhyāyato viṣayān puṁsaḥ saṅgasteṣūpajāyate

Saṅgāt sañjāyate kāmaḥ kāmāt krodho’bhijāyate

Krodhāt bhavati sammohaḥ sammohāt smṛtivibhramaḥ

Smṛti bhramśād buddhināśaḥ buddhināśātpraṇaśyati BGII.62-63

When we humans dwell and focus on things, we become attached to them.

But this attachment does not emerge without its confederates/associates/the fellows of its litter.

From attachment is also born desire, from desire anger – in the broadest sense of perturbation/anxiety/frustration as well as rage – and from anger comes confusion. From confusion, we forget the lessons we have already learnt, our accrued wisdom and discernment is as lost. We lose our ‘connection’ to our buddhi – to the subtlest capacities of our intelligence. When we fall into this cyclic trap of our perturbation/disturbance at our expectations not being met, when our judgment is clouded by anger, envy, anxiety, panic, fear, when we lose connection to our higher capacities, we are lost.

When we lose our connection to buddhi, when we are no longer buddhiyuktaḥ, or integrated: when the light of awareness is no longer illuminating all parts of ourself, we are lost! Running for our lives scenarios aside, if we regress to the level of a frightened mammal, or a cold blooded reptile, we abdicate our true capacities, we lose our humanity, we act ‘beneath’ our true selves. Perhaps you have experienced this a few times in your life, in your own behaviour or in that of others around you. For example, I do not have to make too much effort to recall situations where I acted in ways that did not serve me, or others, and that engendered needless suffering, because I acted not from integration and clear, balanced, integrated intelligence and awareness, but from a fearful, wounded or more primitive place.

To return to Dan Siegel’s memorable phrase to describe our losing our integration and connectedness to our higher, subtler, more complete intelligence: when we ‘flip our lid’, we are no longer as integrated a human being as we already can be, and we are no longer able to draw on the true range of our already activated human capacities. As Kṛṣṇa says, when we lose our connection to buddhi we are lost. When our awareness is clouded and shrouded by anger, anxiety, fear or dejection, we lose connection with our accrued wisdom. We forget the lessons we thought we had already learnt! When this happens it’s a bit like we are bungling and stumbling along back in some prehistoric dark age before we developed a cortex, before we became fully human. But to stay fully human requires effort, and presence. It requires integration. Now perhaps more than ever.

I understand that a century or so ago Rudolf Steiner and Nikola Tesla both spoke about how it was becoming increasingly difficult to be fully human because of the ever-increasing pollution through the elements of existence. Steiner suggested that in order to be human, one would need to redouble the efforts of spiritual practice: of practices that help ‘join us up’ and connect the circuits of our being. One of my Indian teachers more recently said a similar thing:

‘These days the traditional techniques don’t work as they used to, because of the increased pollution in all the elements, so we need to include in our practices regular work to keep cleansing and harmonising the elements of our being. Natural frequencies that previously used to prevail easily once established are now under assault not just from the pollutants in the earth, water, and air, but since the industrial revolution in the element of fire and the realm of kinetic energy, and in the very space we inhabit in the form of all the microwaves and radiation that some of our modern technologies are bombarding our ecosphere with.’

So what to do?

We cultivate the medi-state. With patience and with kindness, with loving presence, we invite all parts of ourselves into the present moment. We practice reinforcing our connectivity, deepening our attunement to our capacity for integration.

As soon as we notice we have become less integrated, or we are not fostering the depth of integration we could, we are empowered. Once we notice, we can do something about it: invite ourselves back into a more gathered, integrated, connected state.

While some external factors may have changed over the centuries, the basic practice of cultivating the medistate, practising gathering ourselves into congruence, tuning the instruments of our being and inviting a state of at-one-ment is perennially valid and helpful. When we are centred, balanced, integrated, we can meet the challenges of life more skilfully.

Further, as the yoga teachings remind us, challenges are really opportunities, and we will never have to encounter anything we are not really ready for. Unexpected challenges are what we have really been preparing for, opportunities to uncover more of who we really are, and recover more of our true capacities. In the Gītā, Kṛṣṇa tells his student Arjuna that the ‘great challenge’ he faces, the situation that renders obsolete the codes and rules he has previously lived by is his ‘lucky day’! What he has been waiting for and preparing for his whole life. Yoga practice is about looking in ways that reach beyond our habitual ways of looking. It’s about thinking in ways vaster than we might previously have dared dream. Challenges that shake our status quo make it harder for us to ignore the whisperings that ‘there may be more to this life’ than I have previously granted space in my attention for.

When we consistently cultivate steadiness, we fortify ourselves to be able to navigate the predictably unpredictable reality of life that little bit more effectively.

When we consistently practice inviting all of ourself into the present moment, we become more attuned to the medistate of integration and wholeness. More attuned to this space of balance, we notice more readily when, how and in what type of situations we allow ourselves to become disconnected. Once we notice, we are empowered to do something about it.

As one of my Indian teachers says: ‘Remember, your problem is smaller than you are! It exists in your awareness.’ When we notice, we are empowered. And we notice more, and more easily when we are connected. So let us maintain awareness of our ‘lid’!

Let us embody sovereign responsibility for the congruence of all the miraculous constituent elements of our being.

Let us work to foster a more robust, resilient and responsive buddhiyuktaḥ state: attuned to conscience and connected to the true depth and breadth of our human resources.

…

Dr Dan Siegel’s video links:

James Boag | Whole Life Yoga

The yoga of the whole human being. Practical philosophy, storytelling, movement, inquiry, looking in ways that reach beyond our habitual ways of looking.

Listen to James’ unique whole life yoga perspectives on the WHOLE LIFE YOGA podcast.