Practical Patañjali – March 2022

Usually when I write about the Yoga Sūtra, it is with commentary and fairly extensive illustration. When I speak about the Yoga Sūtra, I often describe the sūtra-s as being like lighthouses that shine their light out in all directions. They can guide us afresh every time we approach them. They can bring us to useful insights wherever we are on the ‘sea’ of life. And because the Sanskṛt sūtra-s face out in all directions, it makes succinct translation almost impossible. The equivalents a translator chooses almost always lack the same reach or range of connotative and suggestive meaning as the Sanskṛt original. Nor do we even have as distilled a linguistic form as the sūtra in modern languages like English or Spanish for example. However, this morning, not for the first time, I gave a talk on the practical Patañjali, a talk which included a ‘whistlestop tour’ of chapter one of the Yoga Sūtra. Afterwards, while waiting for lunch at the nearby café Espiral, I decided to riff off my, at least for me, relatively distilled presentation, and write a pared back rendering of sūtra-s 1-40, which is where we got to in the hour and forty minute session.

Here it is:

A distilled, interpretative and in some places synoptic rendering of yoga sūtra-s 1-40:

What is the Yoga Sūtra?

In the words of my teacher Larry, ‘the stitches that weave together the fabric of unity. Or as I have come to think of them: the thread we can use to weave greater harmony into the fabric of our lives.

Yoga is practical, so we have to take up the thread. Yoga begins, again and again, when we own that we do not know, when we practice looking in ways that reach beyond our habitual ways of looking. So doing, we make ourselves a patra, a vessel open to receive new insights and assimilate new understandings. Yoga is integration, when we own, acknowledge, integrate all the cyclical, pulsating movements of our awareness. Yoga is harmony, the state of at-one-ment, when all the instrumental powers of our being are tuned to the same key and play as a cohesive orchestra.

Yoga – when all the dynamism of life is brought within the compass of our awareness.

In this state we experience our true essence. Otherwise, our awareness gets congealed and localised in five ways. Our awareness may congeal and localise to accurate or inaccurate perception of what we are experiencing. Yoga is pragmatic with regard to accurate perception – pramāṇa – the means of valid knowledge – and accepts three: direct perception, inference and reliable testimony. Our awareness may also travel on the wings of imagination in the vast realm of vikalpa – association based on language. Or our awareness may be as if absent, as in sleep. Or it may linger in or stray to the past, still attached to memories. The two-fold means to overcome the confinements of awareness and the resulting limited understanding of ourselves and reality is abhyāsa – practice – and the consequent vairāgya.

Abhyāsa is practice: the effort to foster steadiness.

This effort of practice is long-term, uninterrupted, attended to with genuine presence and dedication. In other words, Yoga practice is all the time, is everything we do; the constant, steady, wholehearted effort to cultivate steadiness and wholeness. The practice of wholeness brings Vairāgya – the thirstlessness consequent upon practice. The attachments and allures of the externals that come and go are attenuated by the experience of wholeness that practice invites. Practice works from gross to subtle, inviting us beyond our conditionings and ideas into total presence which re-forms our understanding of who we really are and what we are really made of.

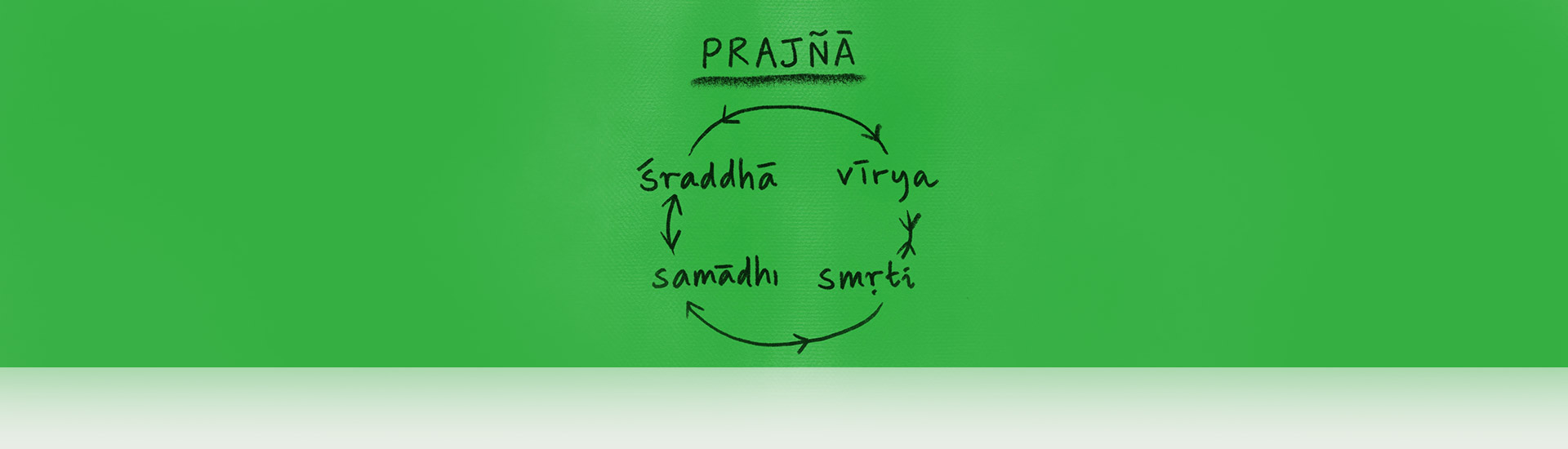

Some beings are born into this state of total presence and unimpeded awareness. For the rest of us, the state of clarified awareness in which our discerning intelligence and intuitive wisdom is no longer impeded by our conditionings is preceded and facilitated by the cultivation of four qualities: Śraddhā – the self-trust, resilience, self-reliance and faith that develops from wholehearted, discerning exploration in the arena of our own lives.

Vīrya – the heroic valour and courage to continue venturing beyond the known, fathoming the shadowlands of our psyches and working to invite deepening integration.

Smṛti: the building of experiential understanding that the heroic, faithful effort is worth it, so we cultivate a memory bank of experience that propels us in the face of doubt; and the re-membering of our innate capacity to experience as a true individual, a person no longer subject to division and fragmentation.

Samādhi – integrated awareness: again and again, inviting all of ourselves into the present moment.

Practice, and practitioners, can be mild, medium, or intense, but when we are truly intent upon it, yoga is right here. Yoga can also be accessed by making all one’s actions a consecrated offering to that which we consider the highest, or to Īśvara.

Īśvara is a consciousness without limit: not limited by having a body, by karma, by knowledge or capacity. Īśvara is the very source of intelligence and knowing, is not bound by time or space, is the intelligence that allows us to learn and evolve, and which always has. Īśvara is beyond name and form. It is connoted by the praṇava, the mantra Auṃ. In other words, Īśvara is everything, from the beginning to the end and everything in between. There is nowhere god is not. By repeatedly reminding ourselves of this we come to understand that everything is divine, everything is the means, all is one.

This deepening recognition dissolves the obstacles to yoga

Physical, mental or emotional imbalance or indisposition, doubt and indecision, carelessness, laziness, negligence or indulgence or lack of respect for the sense powers, attachment to previously experienced states of awareness, expectations and instability of awareness.

These obstacles are overcome by practising wholeness, oneness, integration, balance.

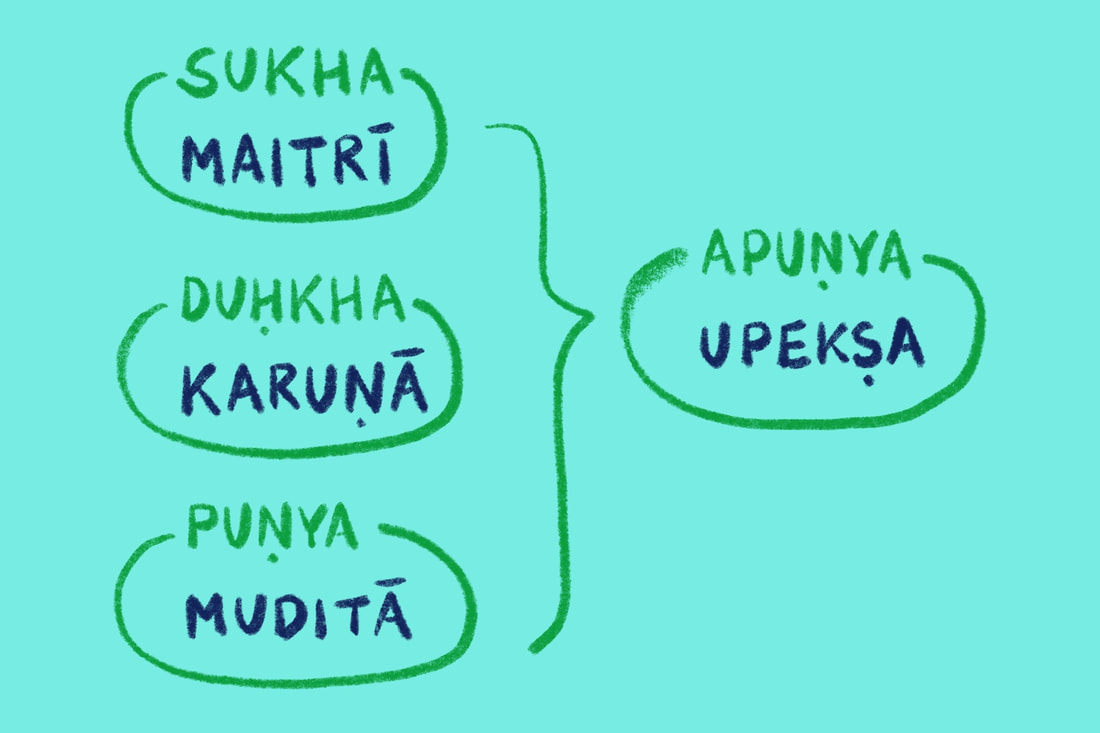

How? The basic practice to clarify our awareness is distilled into four ways of being in response to four types of situation.

In sukha – in agreeable, pleasant situations, when in a good space, with good vibrations, practice maitrī – be friendly, present, open, including to the unexpected gifts that life may offer us in forms different from those we may have imagined.

In duḥkha – in difficulties, pain, suffering, when the vibrations are not so good, practice karuṇā – be compassionate. When encountering beautiful, virtuous, meritorious things, puṇya, practice muditā, joyfulness, let it be a source of inspiration, let it lift you up. And when facing injustice, tyranny, horror, apuṇya, practice upekṣa – be steady, equanimous, practice equipoise and equivision so as to be able to respond most skilfully. Do not let the bad example rob you of your centre.

If one does not automatically respond in these ways in these situations, then we know that we are not established in yoga, so we can keep practising, and Patañjali goes on to offer us a whole ocean of techniques to support practice.

We may take as our support, as our point of focus and orientation for meditation, the movements, pauses retentions of the life force; or we may cultivate greater steadiness and clarity through the instrumental powers and lenses of our awareness by focusing on subtle sense objects; or we can focus on the effulgence beyond all sorrow or desirelessness by meditating on a sage or saint who has realised such a state; or if it happens that god or the guru visits us in dream to initiate us into a practice technique we may use that. Let us practice in a way that works for us.

We will know practice techniques are working when we experience the lens of our awareness becoming clearer and clearer.

James Boag | Whole Life Yoga

The yoga of the whole human being. Practical philosophy, storytelling, movement, inquiry, looking in ways that reach beyond our habitual ways of looking.

Listen to James’ unique whole life yoga perspectives on the WHOLE LIFE YOGA podcast.